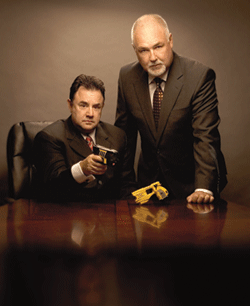

Attorneys Peter M. Williamson(left) and John Burton took the case of a Salinas Man who died of cardiac arrest after being shocked repeatedly with Tasers in a confrontation with police.

© The Daily Journal Corporation. All rights reserved.

Zapping Taser

A SURPRISE PLAINTIFFS WIN HIGHLIGHTS A SCIENTIFIC MYSTERY: WHY DO SOME PEOPLE DIE AFTER BEING SHOCKED REPEATEDLY WITH STUN GUNS?

By Shahien Nasiripour and the Center for Investigating Reporting

Robert and Betty Lou Heston of Salinas were used to violent outbursts from their 40-year-old son. Robert C. Heston had assaulted both of his parents from time to time, once shoving his father to the ground, and in another incident hitting his mother in the face with such force she developed a black eye. His parents attributed the behavior to his addiction to methamphetamines.

On February 19, 2005, Heston, high on meth, physically attacked his then 66-year-old father, knocking him over and dragging him around by one arm. He then punched holes in the ceiling, claiming there was a gunman in the attic. After his father locked him out of their house, he broke a window to get back in. The senior Heston called 911. He thought authorities would lock up his son for a short while, but at least he'd be away from drugs.

Salinas police officers came and left without taking any action. Robert C. Heston wasn't breaking any laws, they said. But the domestic disturbance escalated, and Heston's parents soon called 911 again, this time begging for help. When officers arrived a second time, Heston attacked them, pulling a live outdoor lamp from the wall and throwing it in their direction. In response, five officers shot Heston with Taser stun guns, which are designed for each discharge to deliver a 50,000-volt shock for five seconds. He fell down. During one 74-second span Heston was shocked 25 times, his family says; for much of that time he was lying facedown in the living room. He soon began turning blue, and officers saw that he had no vital signs. Heston was eventually revived and taken to a Salinas hospital, but serious damage had already been done: His heart had stopped beating for at least 13 minutes. He died the next day when disconnected from life support. The medical examiner who performed the autopsy attributed Heston's death to cardiac arrest due to his "agitated state associated with methamphetamine intoxication and applications of Taser."

In the months that followed, Heston's parents expected an apology from police, but it never came. Instead, they received an unsolicited call from Evelyn Rosa, the mother of a Seaside man who had died in 2004 after a similar scuffle with police involving Tasers. Rosa asked the Hestons if they needed a good attorney, and she passed along the numbers of John Burton and Peter M. Williamson, two Southern California lawyers who were representing the Rosa family. Within weeks the two lawyers were representing the Hestons as well.

Last June a San Jose federal jury found that Taser International, manufacturer of the Taser stun gun, was 15 percent liable for Heston's death (Heston v. City of Salinas, No. C 05-03658 (N.D. Cal. 2008)). The jury determined that Taser International knew or should have known that "prolonged exposure" to its stun gun could lead to cardiac arrest, and also that the company had failed to warn Salinas police of that risk. The failure to warn, it found, was a "substantial factor" in causing the police officers to administer a prolonged shock. The jury awarded the Hestons $1 million in wrongful death damages, and it assessed $5.2 million in punitive damages--later struck as a matter of law--against Taser International. The verdict was the company's first courtroom loss, coming after 70 dismissals and settlements.

"It was only a matter of time before they'd lose," Burton says. "If it wasn't us, it would be someone else."

Soon plaintiffs attorneys in law offices around the country were asking how two small-firm practitioners could win a jury verdict against a company that for years had proved invincible to product liability challenges. How had Burton and Williamson broken through Taser International's considerable scientific and legal defenses?

Chief among those defenses had been the company's explanation for deaths associated with stun-gun shocks, which Taser attributes to a phenomenon it promotes as "excited delirium." Burton and Williamson decided to attack the company's theory with their own experts. But to get their experts before a jury, they first had to convince the court that alternative causation theories for Taser-related deaths couldn't be dismissed as junk science.

For 25 years sole practitioner Burton, now 55, has made a practice out of police-misconduct and excessive-force litigation. His law office in a converted Pasadena home consists of himself, a receptionist, a paralegal, and his wife, Sandy. Burton has close-cropped gray hair and a thick goatee, and he is apt to wear Hawaiian shirts to the office. He sports tattoos, speaks directly, and is prone to swearing.

Williamson, 54, is more reserved, choosing his words carefully. His wins include six- and seven-figure settlements in police-misconduct cases, among them a $2 million verdict he and Burton secured in a police shooting case against Ventura County. Williamson is one-half of Williamson & Krauss, a two-person law office in Woodland Hills with limited support staff. In the courtroom, the pair complement each other--the gruff Burton and the dispassionate Williamson.

"We're true believers in the cause," says Williamson, who knew even as a teenager he wanted to practice law, after reading a book by F. Lee Bailey. "It's a righteous way to earn a living. We're not chasing ambulances; we're really doing something that's important."

So is Taser International, say the company and its supporters in law enforcement. Founded in 1993 by brothers Rick and Thomas Smith, the Scottsdale, Arizona-based company manufactures stun guns, intended to be nonlethal alternatives to firearms. The brand name is derived from a loose acronym for the title of a 1911 adventure novel, Tom Swift and His Electric Rifle.

In its first year of sales, Taser became the largest stun-gun manufacturer in the United States, according to court documents filed in Heston. The company's most popular products, the pistol-shaped M26 and X26, are used by more than 13,000 law enforcement, correctional, and military agencies around the world. (Taser products have been brought to market in at least 64 countries.) Taser also manufactures a shotgun model for use in crowd control, and a consumer model for self-defense that comes in various colors.

The Taser M26 and X26 produce electrical shocks that are delivered either through firing darts that remain connected to the gun with insulated wires, or by pressing the stun gun against the subject's body. The stun guns have a range up to 35 feet. When the darts attach to skin or clothing, they create a circuit through which electrical current passes at 19 pulses per second, essentially causing a person to lose body control. According to company cofounder Rick Smith, "[I]t is not the voltage which is dangerous, but rather the current [amperage] that measures both effectiveness and potential danger."

According to Taser's press kit, each shock results in an "immediate loss of the person's neuromuscular control and the ability to perform coordinated action for the duration of the impulse." The shock can be prolonged by either holding down the trigger or pulling it repeatedly. Taser's medical experts contend that such shocks do not affect the heart or other vital organs.

According to the company, its products have saved thousands of lives and reduced injuries to both officers and suspects. As a result, the company claims it has saved law enforcement agencies millions of dollars in workers' compensation claims and settlements arising from excessive-force allegations.

"We've revolutionized law enforcement, and personal safety as well," says Taser spokesperson Steve Tuttle, adding that more than 4,700 agencies across the country now arm all their patrol officers with Tasers.

By all accounts, Tasers are extremely popular with police departments. Company statistics show the stun guns are used about 490 times per day--incapacitating, over the years, more than 1.3 million people. The Cincinnati chief of police, in a 2005 internal newsletter, called Tasers the "only instrument to revolutionize an aspect of policing in the past 35 years."

But there's a serious downside. Since 2001, Amnesty International has recorded more than 340 deaths in North America following police use of Tasers. The United Nations Committee Against Torture last year declared the use of Tasers a form of torture that can kill. The government of British Columbia is currently holding a public inquiry into the safety of the devices, prompted by the Taser-related death of a Polish man at Vancouver International Airport in 2007.

In the past five years, more than 110 lawsuits have been filed against Taser International alleging wrongful death or personal injury. At least 10 of those involving police officers injured during Taser training were settled by the company, according to a 2007 Bloomberg News report; Taser refuses to disclose the precise number of suits it has settled. About 40 product liability suits are pending, Tuttle said in November.

The company has responded aggressively to the accusations. In 2005 it sued an electrical engineer who authored a peer-reviewed study that concluded Taser shocks are powerful enough to kill. That same year, it sued Gannett Co., parent company of USA Today and the Arizona Republic, Taser International's hometown paper, for libel (the suits were dismissed). In May the company persuaded an Ohio judge to order a county medical examiner to remove Taser's name from three autopsies that found the stun gun had contributed to the subjects' deaths. A similar suit against a medical examiner is pending in Indiana.

"Some medical examiners did not understand ... the effect of electricity delivered into the human body and were not aware of the extensive medical studies confirming the safety of the Taser device," says Douglas Klint, executive vice president and general counsel of Taser International. "This ignorance resulted in autopsy errors" mistakenly linking Taser shocks to injuries and deaths.

According to Klint, most of the product liability suits naming the company are part of litigation filed against law enforcement agencies for excessive use of force. Specifically, he says, the suits allege a failure to warn that serious injury or death may result from Taser shocks. But as it turns out, the question of what Taser shocks actually do to the human body is a matter of great legal and medical controversy.

Taser's own experts rely on a theory that the deaths and injuries result not from the shocks but from a state of "excited delirium" in the subjects, a controversial and much-disputed conclusion. Excited delirium is described in a 2006 report on Taser policy and training that was copublished by the Police Executive Research Forum and the U.S. Department of Justice as a "state of extreme mental and physiological excitement, characterized by extreme agitation, hyperthermia, epiphoria, hostility, exceptional strength, and endurance without fatigue."

Klint explains, "Plaintiffs confuse temporal use of the Taser device with causation for subsequent unrelated injuries or death. The fact that a Taser device was used on someone who later died is mistakenly taken as evidence of causation."

The excited-delirium syndrome was first described in 1849 by Dr. Luther Bell, who was trying to diagnose what provoked the otherwise-unexplainable sudden deaths of patients. It gained popularity during the cocaine epidemic of the 1980s, when medical examiners around the country were trying to explain sudden deaths associated with cocaine and crack-cocaine abuse.

The American Medical Association, however, does not recognize excited delirium. Nor is the phenomenon listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders--the chief psychiatric reference used by U.S. mental health professionals--or in the International Classification of Diseases manual.

Critics contend the syndrome is used by police agencies to cover up deaths caused by the use of excessive force. Indeed, because excited delirium is not recognized by the medical community, the International Association of Chiefs of Police advises police departments to use other, more specific terms to explain a subject's in-custody death.

But excited delirium remains central to Taser International's public relations message, and to its defense strategy in court. The company sends out pamphlets to medical examiners and coroners explaining the condition, and the Institute for the Prevention of In-Custody Deaths offers training courses, some of them sponsored by Taser, to help Burton and Williamson's toughest challenge in the Heston case was to counter Taser's excited-delirium theory. The company had scores of medical experts who had produced reports and testified that its devices could not cause a person's death. The attorneys had to offer a new theory-and locate experts who could survive Taser's anticipated challenge to the admissibility of their opinions under Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharms., Inc. (509 U.S. 579 (1993)), the U.S. Supreme Court case that raised the scientific standards for admissible testimony. It was an ambitious undertaking, and a gamble.

"We talked for months about this," Williamson says. "Our simplification of the cause of death was key. If we got bogged down in minutia, we'd confuse the jury. We'd lose the case." First, though, they had to get their theory into court.

Prior to the Heston verdict, Taser had successfully argued that plaintiffs' experts weren't qualified to opine on Taser-related deaths because none of them had published any peer-reviewed studies on Taser stun guns. Critics countered that all the significant research had been funded by Taser. In fact, the company has been so successful at bringing Daubert challenges that in the past five years only one other wrongful death case against it has reached a jury (Taser won).

"We file Daubert motions when appropriate against plaintiffs' experts and move for summary judgment whenever possible," says Klint. "We will appeal any adverse judgment. It is very expensive and very difficult to sue Taser."

But Heston played out differently. At a pretrial hearing last April on Taser's motion to exclude the plaintiffs' experts, the company argued that Heston had been in the throes of excited delirium when he died. No fewer than ten expert reports on Heston's death offered by Taser had concluded that the cause was "excited delirium brought on by his acute and chronic methamphetamine usage," according to testimony by Mark W. Kroll, the head of Taser's Scientific and Medical Advisory Board, who is also a company board member and a paid company consultant.

However, the plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Mark R. Myers, a Pasadena-based cardiac electrophysiologist, was prepared to testify that Taser's stun guns produced Heston's death under several alternative causation theories, including vasovagal reaction, metabolic acidosis, and respiratory acidosis.

Taser's lead attorney--Mildred K. O'Linn, a partner at Manning & Marder, Kass, Ellrod, Ramirez in Los Angeles--petitioned U.S. District Judge James Ware to either exclude the opinions and testimony or conduct a formal Daubert hearing. O'Linn argued that Myers lacked the requisite qualifications and experience, and that his causation theories were not supported by scientific evidence. Without Myers's testimony, O'Linn told the court, "Taser['s defense] is done, because plaintiffs' counsel has simply failed to produce anyone who could testify as to causation in this matter."

Michael Brave, Taser's national litigation counsel, added that Myers wasn't qualified to testify because he had "stated in his deposition that he was not an expert in the field of electronic control devices, Taser devices, or the effects of Taser devices." Indeed, Myers had based his conclusions in part on published studies of the effects of Tasers on pigs.

O'Linn argued that citing animal research failed to pass muster under Daubert. "There is direct legal authority that says animal studies do not directly correlate to human effects," she told Judge Ware.

"That's something you can tell the jury about," Ware responded. "It does seem to me that many breakthroughs in science have been based upon animal studies, and so I won't reject the idea that animal studies can inform opinion with respect to the effect in human beings, especially since I know that pig studies are regularly used for studies of the effect of the devices in human beings."

After denying O'Linn's motion, Ware told her, "You can criticize [Myers] up one side and down the other, and call in contrary witnesses to show the unreliability of his opinion. But it does seem to me that if he has a basis, weak though it may be, I have to allow him to express it even though it's tantamount to saying you can get brain tumors from standing under a tree--and I'm not sure that you're in that far-fetched an area."

The causation theory Burton and Williamson eventually presented to the jury focused on the intense muscle contractions produced by Taser shocks. Muscle contractions produce lactic acid; that's why Taser shocks can be dangerous when applied repeatedly. Because subjects don't have control over those muscle contractions, they can't slow down their movements or increase oxygen intake--as an athlete might--to counter the buildup of lactic acid. Too much lactic acid in the body produces acidosis, and critical proteins start to break down. Cardiac arrest can result. Untreated, it kills within minutes.

Heston was shocked 25 times in a span of 74 seconds, the plaintiffs contended. Muscle contractions from those repeated 50,000-volt discharges, they argued, led to his cardiac arrest. Dr. Myers noted in correspondence to Burton that Heston's blood readings showed severe metabolic acidosis. "Our theory was the secret to our success," Burton says. "Everybody understands the concept. We distilled something that was very complex into something that was very simple."

Taser International contended that Myers's acidosis theory was simply wrong, and "wholly lacking in scientific support and reliability." It countered his responses to questions during deposition with the opinions of its own expert, Kroll--an electrical engineer with patents for numerous electrical medical devices but no medical degree.

At trial, the company cited studies showing that people being shocked by a Taser continue to breathe. Brave says that subjects actually breathe heavier and deeper, which, he contends, counters any acid buildup. "A Taser discharge helps respiration," Brave says, citing several company-funded studies. "Exercise is far more harmful to you."

In court Burton and Williamson argued that because the studies Taser cited most had been paid for by the company, the medical experts who conducted those studies--and their findings--were tainted.

Taser originally told Ware that it would present testimony by 15 experts from around the country. Burton and Williamson objected that the plaintiffs were being asked to bear unreasonable costs to depose all of those experts. So Ware ordered Taser to pay the plaintiffs' costs for deposition.

Ultimately, neither side was able to conclusively show what causes Taser-related deaths.

Dr. Zian H. Tseng, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor at UC San Francisco Medical Center, conducted his own Taser study, which is awaiting publication in a peer-reviewed medical journal. "It's difficult to prove definitively that the Taser was a direct cause of death," says Tseng. "But there's a lethal risk--a small risk, but a lethal one. They should be used cautiously and judiciously. Without that knowledge [of the potential risks], they're going to be used irresponsibly."

"Until there's been enough testing of Taser applications on heart rhythm, opinions are speculative," says Keenan Nix, a plaintiffs attorney at the Atlanta office of Morgan & Morgan, who has a pending case against a hospital following the death of a man shocked repeatedly with a Taser. "There is a temporal link. When you have folks dropping like flies within moments of a Taser application, there is a commonsense causal connection. What we're finding is that the number of experiments regarding the connection between the Taser and heart rhythm is sparse." Nix recently dismissed Taser as a defendant in what he described as a "business decision."

Still, Myers is convinced there's a causal link in the Heston case. "All people with methamphetamine intoxication do not die of the methamphetamine or of 'excited delirium,' " he wrote in his review of Taser's experts. "In the [Heston] case the only significant adverse physical stimulus was from the Taser applications. Are we really expected to believe that the Taser has no physiologic effects when delivered in the manner of this case? If so, then if the police had simply waited outside for 5 to 10 minutes, this man would have died spontaneously. I could not explain such a death."

Burton and Williamson were able to offer the jury alternative causation theories to explain Heston's death. But this was a product liability suit: Its two principal causes of action were negligence, and strict liability for injuries caused by defective and dangerous products. The suit alleged that Taser International had failed to warn the city of Salinas of the dangers associated with using its stun guns. A manufacturer's risk of being sued is substantially reduced or eliminated if it presents such warnings, says J. David Prince, a professor at William Mitchell College of Law in St. Paul, Minnesota, and coauthor of the Products Liability Prof Blog. But the warnings must be strong enough to effectively communicate the dangers associated with use of the product.

In fact, as lawsuits have accumulated, Taser's product warnings have shifted noticeably over the years. According to Burton and Williamson, Taser first warned of dangers associated with multiple, prolonged exposures in a PowerPoint presentation shipped to law enforcement customers in January 2005--about five years after introduction of the M26 model that was fired at Heston. The warning was on slide 108 of a 174-slide presentation. The Heston incident occurred the following month. But the city of Salinas argued in court filings that its police officers were never advised that "multiple Taser deployments or multiple cycling would create a health risk." The Salinas Police Department first purchased Tasers in 2003.

Burton and Williamson also contended that Taser never warned officers that multiple Taser shocks could lead to acidosis, or to cardiac arrest. Four months after Heston's death, however, Taser released a training bulletin that cautioned: "Repeated, prolonged, and/or continuous exposure(s) to the Taser electrical discharge may cause strong muscle contractions that may impair breathing and respiration. ... Users should avoid prolonged, extended, uninterrupted discharges or extensive multiple discharges whenever practicable ... particularly when dealing with persons showing symptoms of excited delirium ... [who] are at significant and potentially fatal health risks from further prolonged exertion and/or impaired breathing."

As a public relations matter, the additional warnings backfired--news reports focused on the phrase "potentially fatal health risks." Five weeks later, Taser International President Thomas Smith issued a clarification: "The bulletin never indicated that our technology has caused death; rather the media has somehow managed to distort and misrepresent this commonsense guideline into a sensational and misleading story that could have serious adverse consequences on the safety of law enforcement officers and citizens."

Professor Prince says that Taser's revised training bulletin probably would shield the company from subsequent failure-to-warn suits, but also that the company could still be on the hook for incidents that occurred before publication--such as the one involving Heston.

In addition, Prince says, changes in Taser's marketing--which parallel revisions in its product warnings--may have created even more legal risk for the company. In a 2002 report to the Securities and Exchange Commission, for instance, Taser branded itself a manufacturer of "less lethal" weapons. The "less lethal" designation continued until April 2004, when Taser began describing its products as "non-lethal" weapons. The next year, the Department of Defense issued a report that classified both the M26 and X26 stun guns as "non-lethal," which in DOD terminology means they're not intended to be fatal.

In September 2005 the Arizona attorney general's office, which had been investigating Taser's safety claims, reached an agreement with the company limiting its use of the word non-lethal; the company agreed to qualify the term by including the Defense Department's definition. That same month, Taser announced the results from another study--which it partly funded--that indicated people subjected to Taser shocks not only continued to breathe but had higher breathing rates and volumes during the exposure. The announcement dropped all reference to "non-lethal." Taser now describes its stun guns as "generally recognized as a safer alternative to other uses of force."

To the ACLU of Northern California, Taser's semantic changes appeared to be calculated. "When Taser labels its weapon non-lethal," the organization contended in a 2005 report, "it is merely saying that the stun gun is less lethal than a firearm, not that it is non-lethal as commonly understood by law enforcement or the general public."

Taser CEO Rick Smith, however, asserts that less lethal and non-lethal are synonymous. "There was no specific policy decision [to change the language]," he claimed in a July 2005 deposition in another case. "We were not recharacterizing ... the weapon, but rather adopting the standardized Department of Defense definition in using non-lethal."

Prince comments, "It's a mixed message. As a product manufacturer, I could later make the argument that, 'Yes, I showed these ads, but I warned later on.' There's at least a jury question there, and I don't know that I'd want a jury to decide that."

This past April, Taser rescinded the warning against prolonged exposures in its 2005 training bulletin, citing new medical and scientific evidence that its stun guns do not impair breathing, affect the heart, or cause ventricular fibrillation, and that exposures up to 15 seconds do not cause metabolic acidosis.

The controversy over science, warnings, and marketing coalesced in Heston. Taser contended that it didn't have to warn law enforcement agencies that its weapons might cause death because no reputable scientific or medical evidence indicated that they could--and no jury had found otherwise. The company also insisted there was no significance to changes in the wording of its training bulletins and marketing kits.

The Heston jury disagreed. After two and a half days of deliberation, it returned a defense verdict in favor of the Salinas Police Department and a plaintiffs verdict against Taser International. The jury found that multiple Taser shocks can cause acidosis, and that acidosis can lead to fatal cardiac arrest. It also concluded that Taser had failed to warn police of this possibility. The jury awarded compensatory damages of $21,000 to Heston's estate and wrongful death damages of $1 million to his parents, apportioning 85 percent of the fault of Robert C. Heston's death to his behavior and 15 percent to Taser for negligently failing to warn about the risks of its M26 stun gun. Finally, it assessed $5.2 million in punitive damages against Taser International.

More than anything else, it was the failure to issue adequate warnings that tripped up the company in court, says Robert Haslam, a Texas lawyer and chair of the Taser Litigation Group at the American Association for Justice in Washington, D.C. "Taser absolutely created its own problems," he argues. "If they [had] warned properly, it would have changed the situation dramatically. Taser would've relieved a lot of its present problems."

For Burton and Williamson, the victory in Heston didn't come cheap. The pair put in approximately 2,500 hours on the case and accrued out-of-pocket expenses of $200,000, according to their fee application.

But the plaintiffs bar was encouraged. "My God, my confidence went up!" says Waukeen Q. McCoy, principal at McCoy & Associates in San Francisco, who has a pending wrongful death case against Taser. "It was very helpful. I think Taser thought it was invincible before this verdict."

"[The plaintiffs' team] had really good discovery, and they were good at getting expert witnesses to debunk the information Taser puts out," says John L. Burris, a sole practitioner in Oakland who has settled at least two Taser-related cases with California cities. "Taser has done a pretty good job of co-opting the experts," he adds.

The defense bar also took notice. "There's blood in the water," says Ted Frank, an attorney and tort reform advocate at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C. "The plaintiffs bar has targeted Taser. They were a little deterred before, but now they're going to attack. Taser has a tough decision to make: Does it fight or settle? The danger is you can get a feeding frenzy when you settle."

Although Taser took the brunt of the Heston verdict, that may have been by its own design. In a bulletin to its law enforcement customers a week after the verdict, Taser reassured police that its top priority in such litigation is to see that "the police officers involved ... were not 'scapegoated' in any way. This strategy included Taser International taking some additional risk at trial"--an apparent reference to the company's active support of efforts to gain qualified immunity for police officers involved in the incident. Describing its approach as "the right thing to do," the company noted, "This case is a reminder of the inherent risks involved in jury trials, regardless of the strength of evidence and facts. It is widely understood within the legal community that juries are unpredictable."

The company holds firm to its contention that Heston died from excited delirium. Taser General Counsel Klint asserted in a company release in June, "The Taser [stun gun] was not a causal factor in this death, which fit the well-established symptom pattern for methamphetamine intoxication and associated excited delirium."

Since the Heston verdict the company's fortunes have improved. In June the U.S. Department of Justice released initial findings from a study of Taser-related deaths that concluded "law enforcement need not refrain from deploying [Tasers]." The report found "there is no conclusive medical evidence within the state of current research that indicates a high risk of serious injury or death from the direct effects of [Taser] exposure." However, the report did caution against multiple, prolonged Taser shocks, noting that their medical risks are "unknown" and "the role of [Tasers] in causing death is unclear." The final report is scheduled for release next year.

The Rand Corporation also released a report on Tasers, this one requested by the New York City Police Department after a confrontation in which a groom-to-be died in a hail of 50 police bullets. Rand recommended that the NYPD consider using Tasers instead of firearms in more situations, under a pilot program to test the device's effectiveness. But those recommendations were undercut in September when an NYPD officer used a Taser on a deranged man standing on a balcony, who then fell to his death. Days later, the despondent officer committed suicide.

Then in October, Judge Ware struck down the punitive damages against Taser in Heston as a matter of law. Only about $153,000 in total compensatory damages remained--not even enough to cover Burton and Williamson's expenses, let alone their hours.

But the ruling on punitives wasn't entirely a victory for the defense. Judge Ware wrote in his order, "The Court finds that there was substantial evidence ... that under certain conditions, prolonged exposure to electronic control devices posed risks to human health ... that a reasonable manufacturer would have warned of those risks ... [and] that Taser failed to give an adequate warning and that this lack of warning led the Salinas police officers to make prolonged deployments against Robert C. Heston." He cited plaintiffs' evidence that warning about "prolonged deployment" of the weapons "was not done in a way that would capture the attention of customers."

Because Judge Ware's ruling--related to errors in his jury instructions--was based on a matter of law, Burton says, it doesn't take away from the jury's verdict that Taser was partly liable for Heston's death.

"We've proven that Tasers can kill," Burton says, "and that [Taser International's] warning and training structure is inadequate. It was clear what the jury wanted to do: They wanted to send a message to Taser. That's a final judgment."

In the immediate weeks after the Heston verdict, Burton and Williamson had speculated that Taser International might be more inclined to settle claims, citing their own discussions with the company in the case of Evelyn Rosa's son. But no more: As of late fall, the duo said, Taser's lawyers are as aggressive as ever, and have not shown the least interest in settling.

One of those cases involves a 17-year-old North Carolina boy who died after being shocked by a Taser for 37 seconds in a Charlotte grocery store. Much of the incident was captured on videotape by the store's security cameras. An autopsy revealed that the boy died from cardiac arrest, though he had no drugs in his system, nor any previous heart problems. The coroner concluded in his autopsy report, "This lethal disturbance in the heart rhythm was precipitated by the agitated state and associated stress as well as the use of the conducted energy weapon (Taser) designed for incapacitation through electromuscular disruption."

Taser counsel Brave sees other hazards as a result of the verdict. "What is it gonna cost in terms of officers who are now hesitant to use the device, and the deaths that can result from that hesitation?" he challenges. "Ask the officers, and see what they have to say about medical examiners who put down things in their reports that are unsupported. You've got to understand the science."

In Salinas, Chief of Police Daniel Ortega contends that Heston would have died regardless of the Taser shocks. Neither Heston's death nor the jury verdict has diminished his confidence in the weapon. Since the department added Tasers to its arsenal in 2003, he says, it's seen 81 percent fewer officer injuries and a 33 percent drop in injuries to suspects. Indeed, Ortega says he wants to buy more Tasers, particularly the updated X26 model, which features a mounted camera.

With six cases against Taser International currently scheduled for trial--the first of which began in November--the company will have ample opportunity to retest its theory of excited delirium. Soon enough, it will know whether the Heston verdict was an aberration, or a sign of things to come.

Shahien Nasiripour is a fellow at the Center for Investigative Reporting in Berkeley.